Last Light, 2016

For anybody presently practicing analogue photography, it is not unusual to be given out-dated photographic equipment. People are all-to-happy to know “old-school” photographers, on whom can be dumped endless amounts of expired paper, film, and chemistry. We are crushed beneath a landfill’s-worth of rattling enlargers, dusty boxes, moldy manuals, cracked safelights, and stained trays, and in the process we forestall people’s guilt about filling dumpsters. Oftentimes we can’t throw this stuff away, knowing what it would have cost — at one time — to buy new, or we simply file it under (a bottomless pit): this might be useful some day. This fatal threshold, drawn between accepting/refusing is that which keeps the artists penned safely away from professionals.

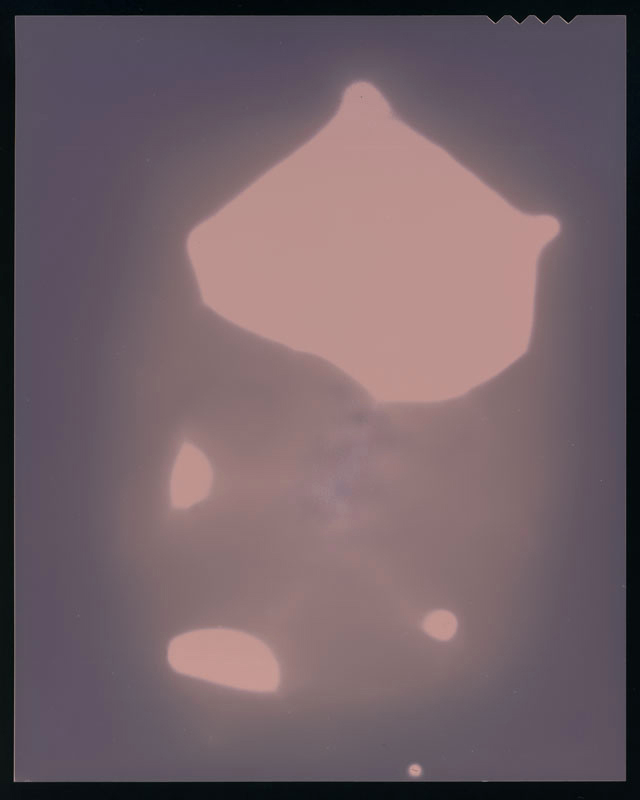

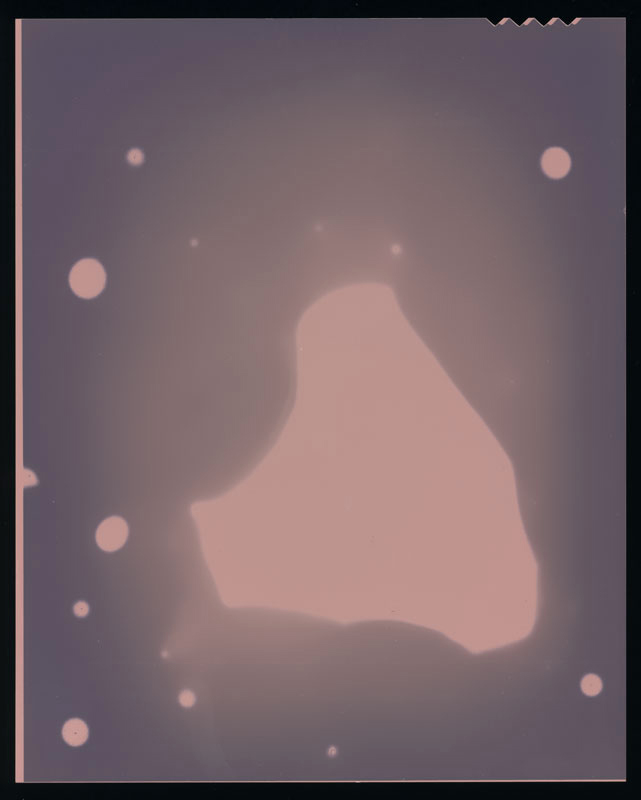

It was in this spirit that I blithely accepted some box of something from some unremembered person. In it was a windfall of old 4” x 5” film. Though the boxes of film were in varying states of disrepair, they were all merrily beyond their expiry dates. One box of 100-speed T-Max seemed redeemable, but when I opened it and examined it by feel in the dark, I discovered that moisture had stuck the five remaining sheets together. I decided to conduct an experiment. In a pitch-dark room, I separated each of the five sheets, and placing them on a scanner bed, I scanned them at high resolution. In the same instant that the film was visually recorded, it was destroyed — thoroughly exposed to light. What I came away with were the first and, in a sense, the final glimpses of this sheet-film as film, with its accordant photographic potential. At that moment, the film left the realm of tool and entered the into the realm of object.

What I got for my efforts was a small series of photographic readymades. The moisture that had invaded the box of film had wrought abstract forms — auratic blobs that ranged from the biological to the celestial. Some combination of chemical (silver), biological (gelatin), and elemental (moisture) forces had worked on the film on a visual level. One sheet was left largely unaffected by the moisture, though a thumbprint (whose?) was made manifest at one edge. The sheets of film affected one another in ways that seemed at once both scientific and mysterious. Ultimately, the images of the five sheets of film became a rich metaphor at the heart of all these binaries: life/death, light/dark, tool/object, outmoded/relevant.

“”