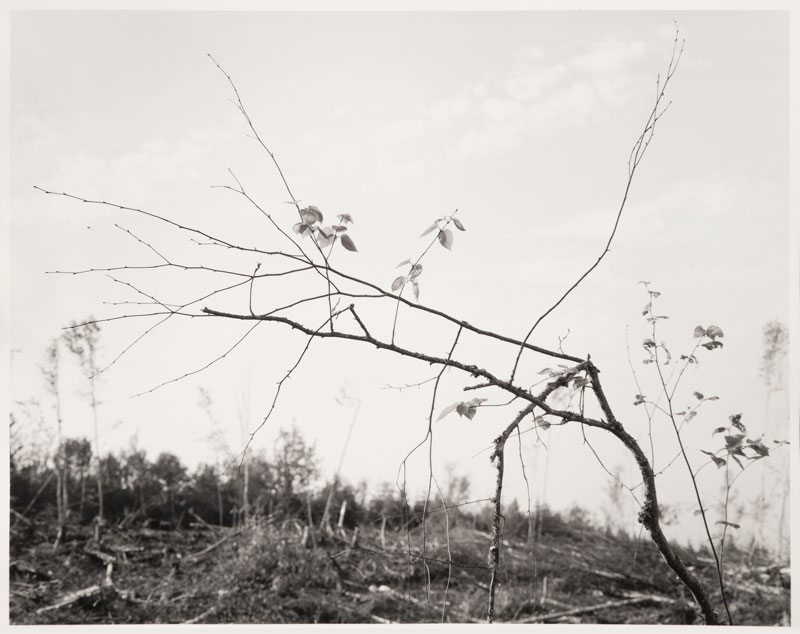

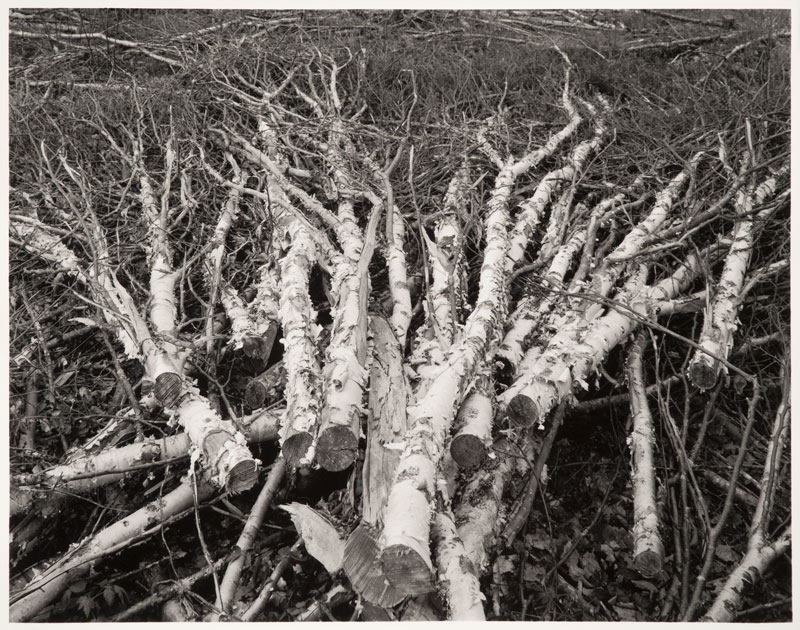

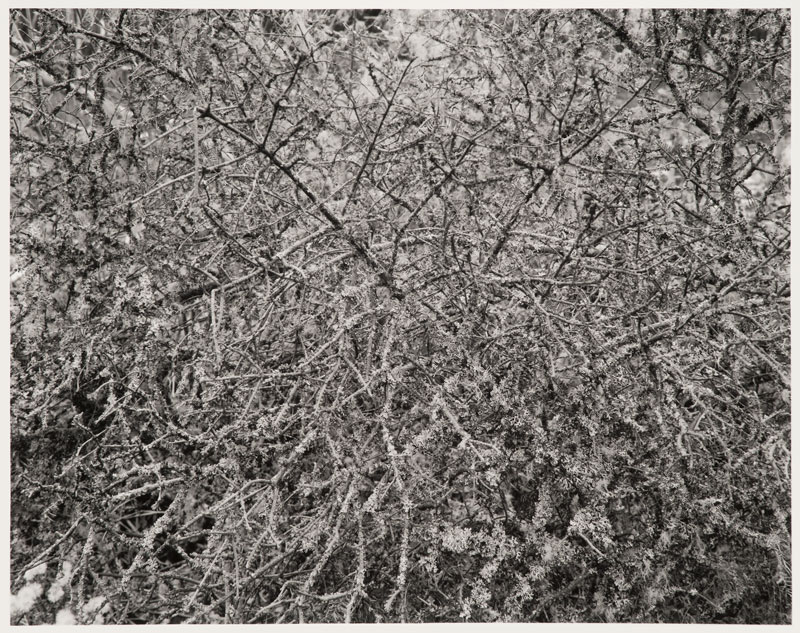

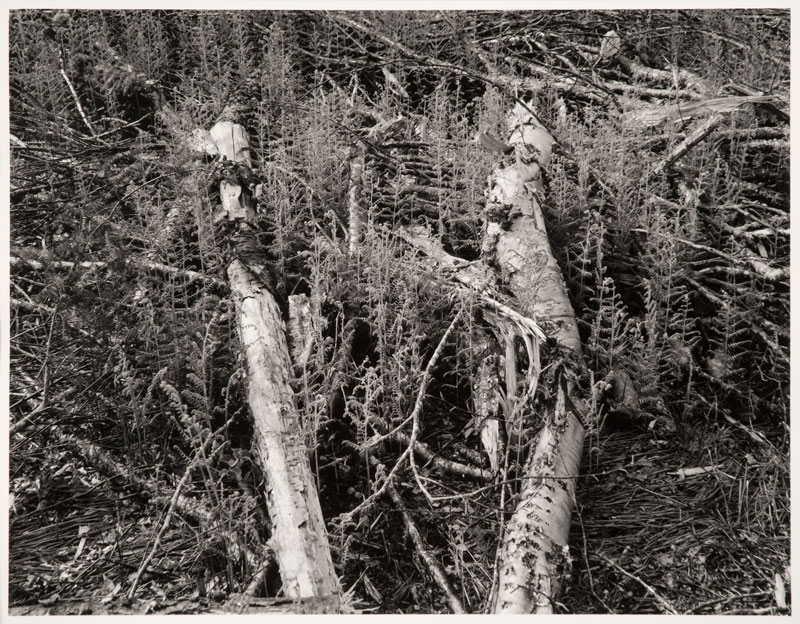

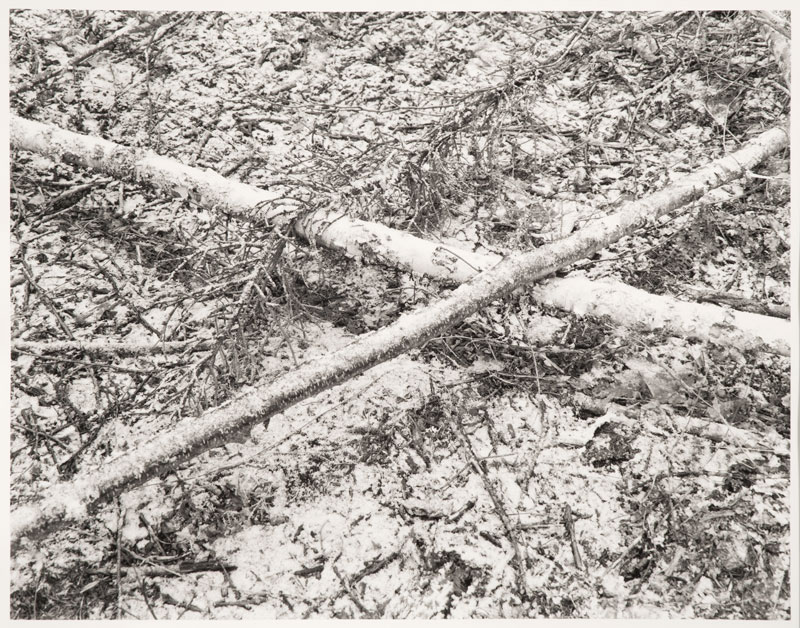

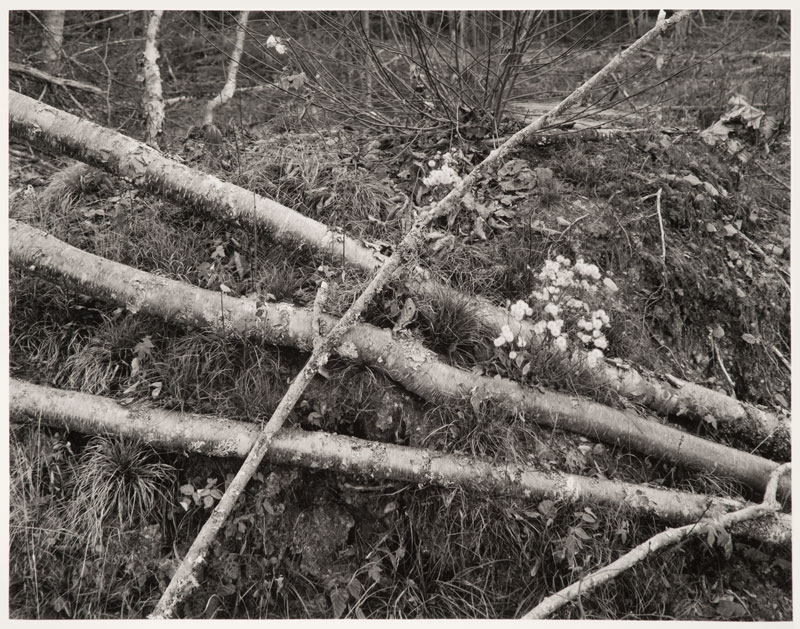

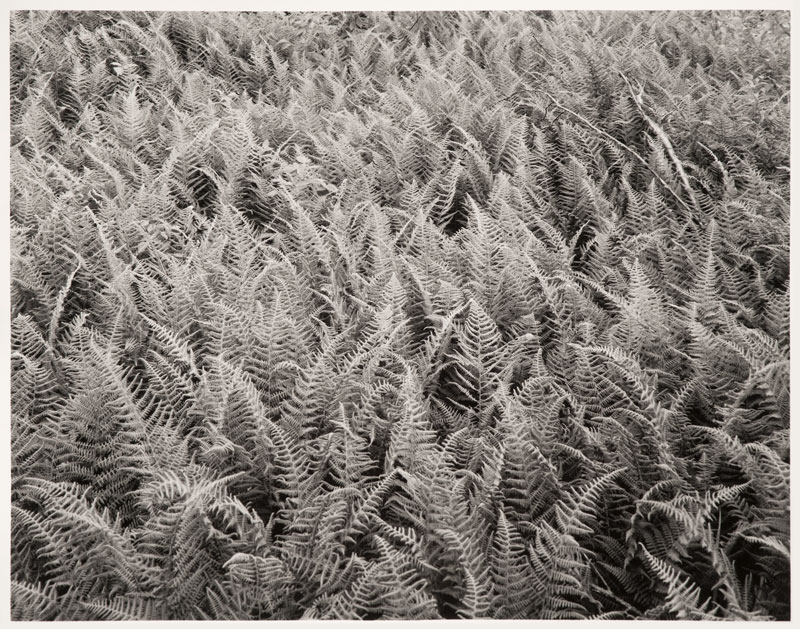

Clearcut, 2005-6

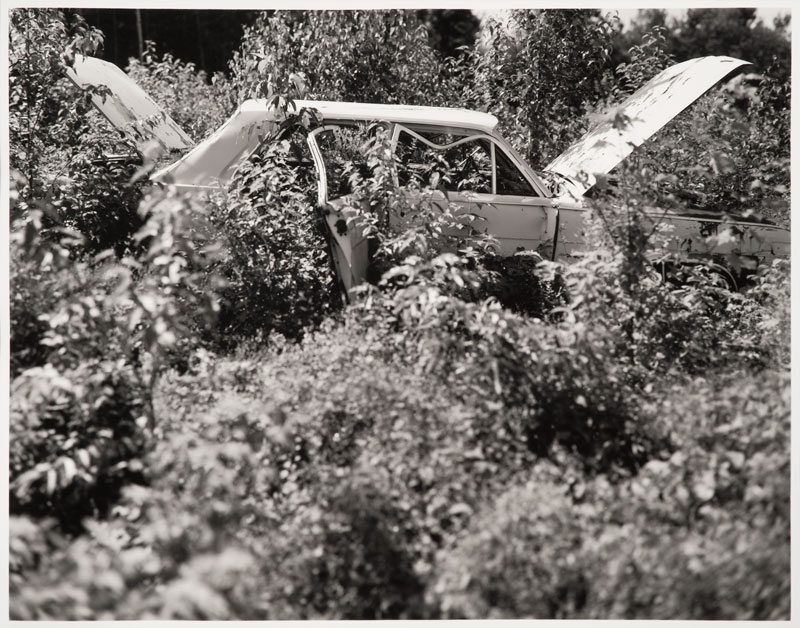

In 2005, I was living in Sackville, New Brunswick. Driving out of town on a familiar stretch of the Trans-Canada Highway, I noticed, for the first time, a flash of robin’s-egg blue in the landscape. That colour belonged to a 1966 AMC Rambler Ambassador sedan, abandoned, in the middle of a clear-cut forest. The car must have been there a very long time, and I noticed it only because the forest had just been cut down around it.

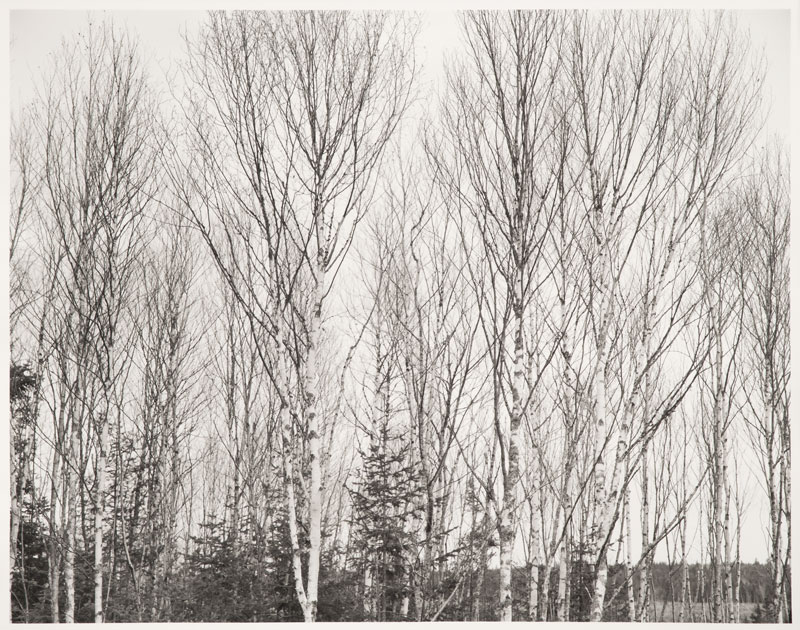

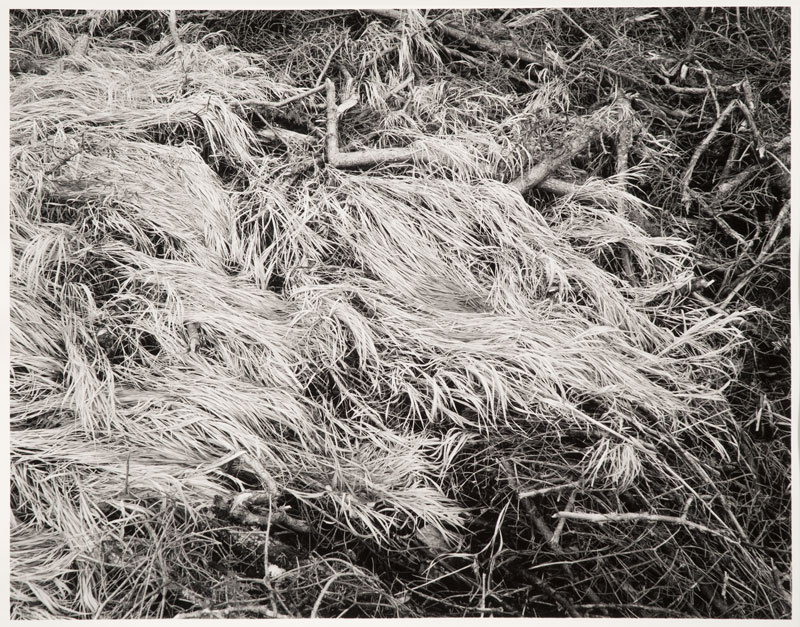

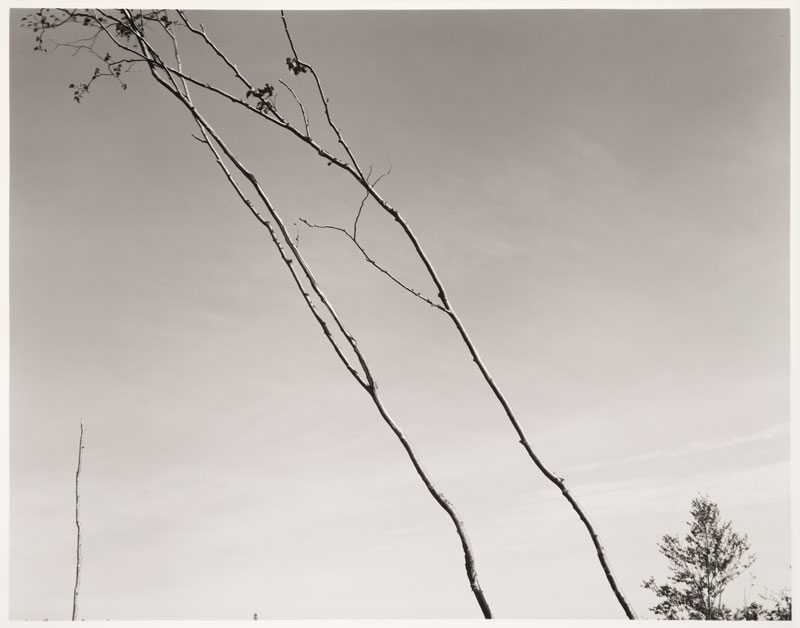

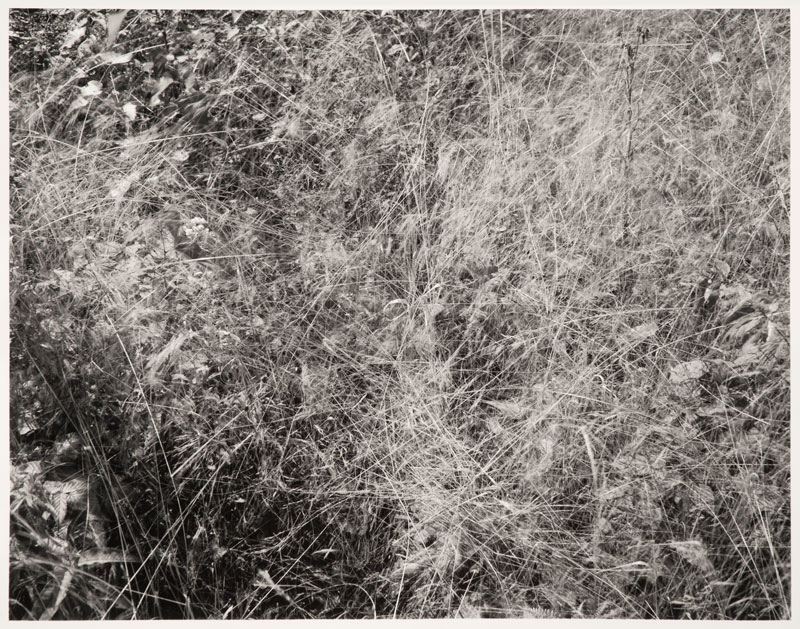

Logging can be ferocious, anywhere, but New Brunswick is notable for how much of its forest is “harvested” to then be replanted with monocultures, effectively converting natural, diverse forest systems into tree plantations. Thus my initial reaction was one of rage, and I set out to make a document of the new, shorn landscape using the exacting scrutiny of an 11” x 14” view camera. The cumbersomeness of this large apparatus meant that I moved around the clear-cut very slowly, deliberately, fishing for compositional order in a completely disordered landscape. It was important that the point of view be an intimate one, made from the height of an average human vantage. The emotional response that propelled me into that landscape very quickly subsided into a contemplation of our use of, impact on, and place within, the natural world.

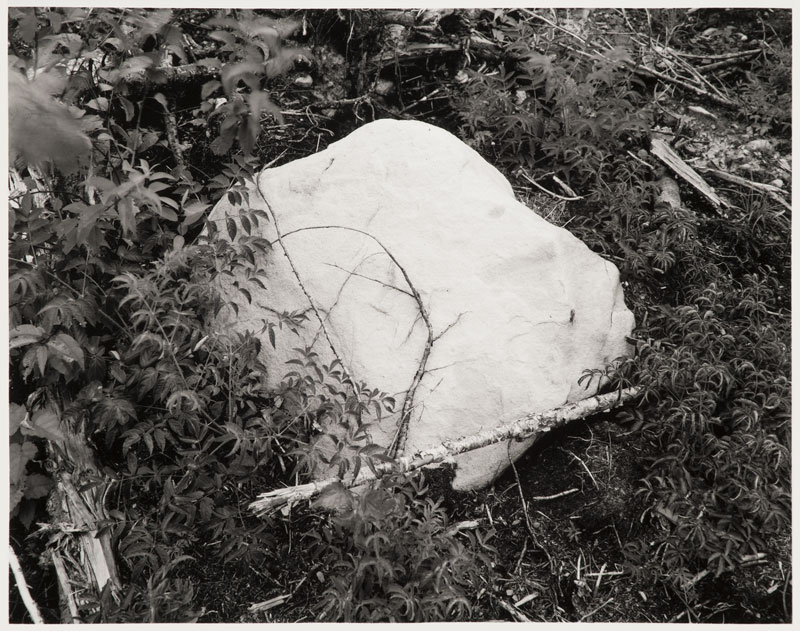

The fundamental irony of this transformed landscape was that while it was a completely natural space, it was also an industrial byproduct. Aside from the vandalized car and the remnants of a campfire, the only traces of human presence were the marks that were there to be seen — the deep impressions of skidder tires, the arcing saw cuts that the giant harvesters had left across the end-grains of stumps. The skidder tracks became provisional streams, filling with water that ran down the slope of the land. The stumps became sacrificial platforms on which squirrels left their midden piles of chewed cones.

I spent fourteen months photographing the forest’s response to being cut, seeing what would happen in a little over one full cycle of the seasons. Clearcut began as a meditation on a natural environment that was exploited by human industry. At some point near the end of the project, realizing that the blue car had effectively been swallowed by the green of new life, it became obvious that our focus on environmental protection, while vitally important, becomes a distraction from our own species’ precariousness. As I consider this idea eleven years later, it dawns on me for the first time how prescient and apposite it was that the wrecked car — the clear-cut’s one artifact of human making — bore the name Ambassador.

The series Clearcut consists of forty-three 11” x 14” toned silver gelatin contact prints, printed in an edition of five.